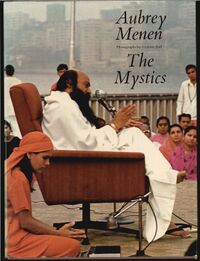

The Mystics

- This is a rare 1974 hardcover book about Indian mystics at that time. One chapter is devoted to Osho and contains many photos from a meditation event in Bombay, with the first Westerners showing up.

- author

- Aubrey Menen

- language

- English

- notes

- For the text of the chapter on "Rajneesh": see below.

editions

The Mystics

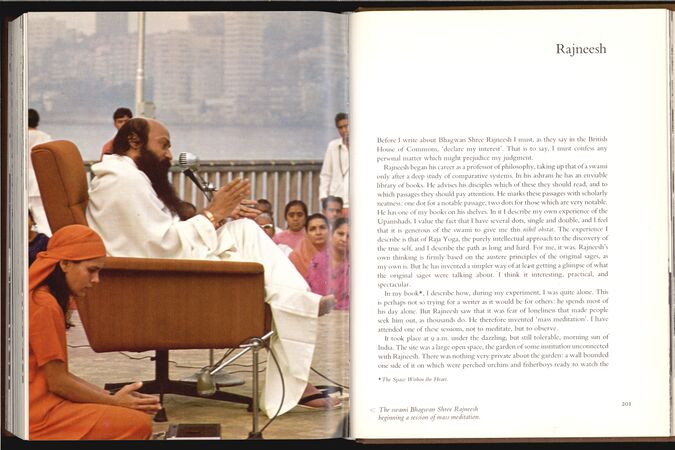

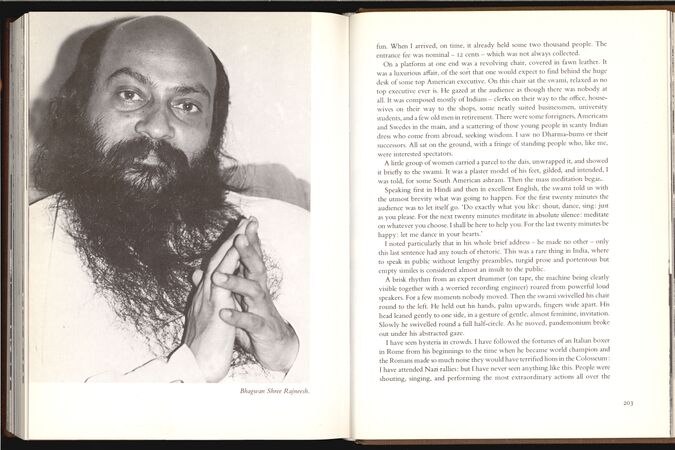

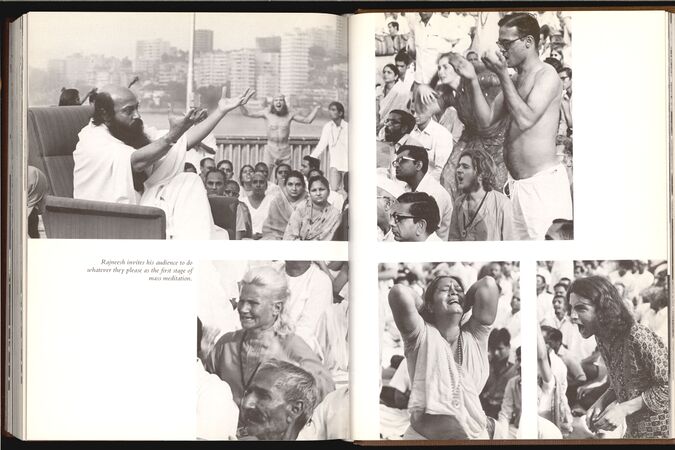

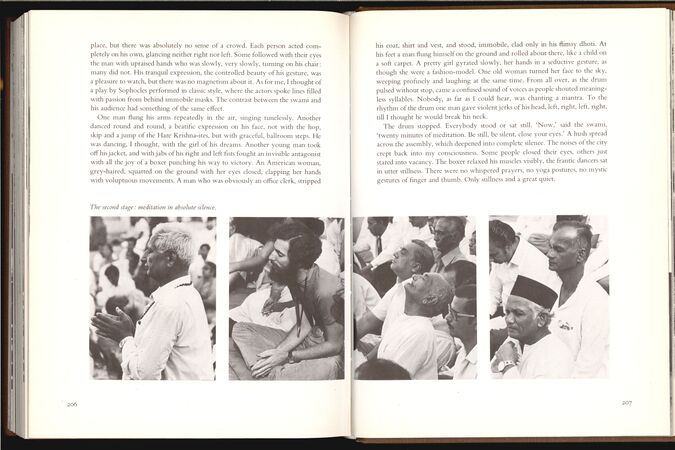

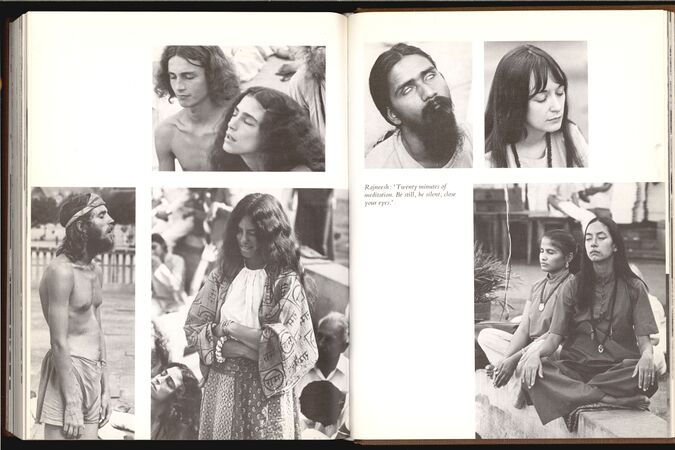

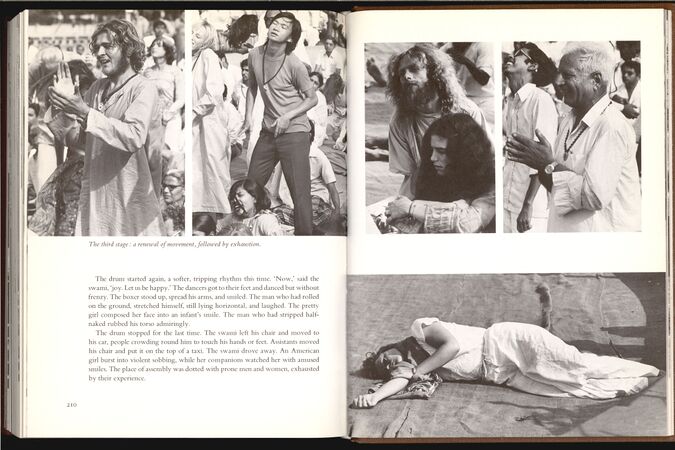

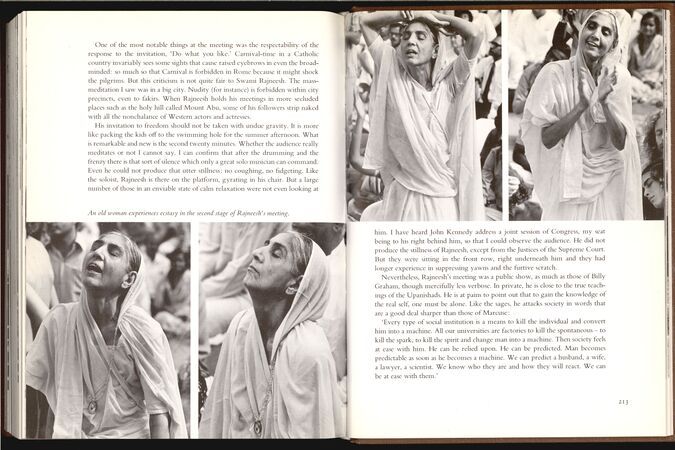

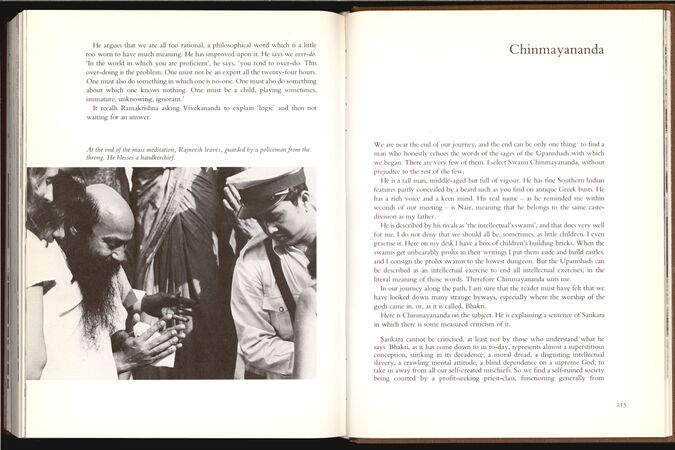

p.002 - 003 Title page. p.004 - 005 Table of contents 1. p.006 - 007 Table of contents 2. p.200 - 201. Photo caption: The swami Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh beginning a session of mass meditation. p.202 - 203. Photo caption: Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh. p.204 - 205. Photo caption: Rajneesh invites his audience to do whatever they please as the first stage of mass meditation. p.206 - 207. Photo caption: The second stage: meditation in absolute silence. p.208 - 209. Photo caption: Rajneesh: "Twenty minutes of meditation. Be still, be silent, close your eyes." p.210 - 211. Photo caption: The third stage : a renewal of movement , followed by exhaustion. p.212 - 213. Photo caption: An old woman experiences ecstasy in the second stage of Rajneesh ’ s meeting. p.214 - 215. Photo caption: At the end of the mass meditation, Rajneesh leaves, guarded by a policeman from the throng. He blesses a handkerchief. |

Chapter: Rajneesh

- p.201

- Before I write about Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh I must, as they say in the British House of Commons, ‘ declare my interest ’ . That is to say, I must confess any personal matter which might prejudice my judgment.

- Rajneesh began his career as a professor of philosophy, taking up that of a swami only after a deep study of comparative systems. In his ashram he has an enviable library of books. He advises his disciples which of these they should read, and to which passages they should pay attention. He marks these passages with scholarly neatness: one dot for a notable passage, two dots for those which are very notable. He has one of my books on his shelves. In it I describe my own experience of the Upanishads. I value the fact that 1 have several dots, single and double, and I feel that it is generous of the swami to give me this nihil obstat. The experience I describe is that of Raja Yoga, the purely intellectual approach to the discovery of the true self, and I describe the path as long and hard. For me, it was. Rajncesh ’ s own thinking is firmly based on the austere principles of the original sages, as my own is. But he has invented a simpler way of at least getting a glimpse of what the original sages were talking about. I think it interesting, practical, and spectacular.

- In my book(*1), I describe how, during my experiment, I was quite alone. This is perhaps not so trying for a writer as it would be for others: he spends most of his day alone. But Rajneesh saw that it was fear of loneliness that made people seek him out, as thousands do. He therefore invented ‘ mass meditation ’ . I have attended one of these sessions, not to meditate, but to observe.

- It took place at 9 a.m. under the dazzling, but still tolerable, morning sun of India. The site was a large open space, the garden of some institution unconnected with Rajneesh. There was nothing very private about the garden: a wall bounded one side of it on which were perched urchins and fisherboys ready to watch the

- (*1) The Space Within the Heart.

- p.203

- fun. When I arrived, on time, it already held some two thousand people. The entrance fee was nominal - 12 cents - which was not always collected.

- On a platform at one end was a revolving chair, covered in fawn leather. It was a luxurious affair, of the sort that one would expect to find behind the huge desk of some top American executive. On this chair sat the swami, relaxed as no top executive ever is. He gazed at the audience as though there was nobody at all. It was composed mostly of Indians - clerks on their way to the office, house ¬ wives on their way to the shops, some neatly suited businessmen, university students, and a few old men in retirement. There were some foreigners, Americans and Swedes in the main, and a scattering of those young people in scanty Indian dress who come from abroad, seeking wisdom. I saw no Dharma-bums or their successors. All sat on the ground, with a fringe of standing people who, like me, were interested spectators.

- A little group of women carried a parcel to the dais, unwrapped it, and showed it briefly to the swami. It was a plaster model of his feet, gilded, and intended, I was told, for some South American ashram. Then the mass meditation began.

- Speaking first in Hindi and then in excellent English, the swami told us with the utmost brevity what was going to happen. For the first twenty minutes the audience was to let itself go. ‘Do exactly what you like: shout, dance, sing: just as you please. For the next twenty minutes meditate in absolute silence: meditate on whatever you choose. I shall be here to help you. For the last twenty minutes be happy: let me dance in your hearts.’

- I noted particularly that in his whole brief address - he made no other - only this last sentence had any touch of rhetoric. This was a rare thing in India, where to speak in public without lengthy preambles, turgid prose and portentous but empty similes is considered almost an insult to the public.

- A brisk rhythm from an expert drummer (on tape, the machine being clearly visible together with a worried recording engineer) roared from powerful loud speakers. For a few moments nobody moved. Then the swami swivelled his chair round to the left. He held out his hands, palm upwards, fingers wide apart. His head leaned gently to one side, in a gesture of gentle, almost feminine, invitation. Slowly he swivelled round a full half-circle. As he moved, pandemonium broke out under his abstracted gaze.

- I have seen hysteria in crowds. I have followed the fortunes of an Italian boxer in Rome from his beginnings to the time when he became world champion and the Romans made so much noise they would have terrified lions in the Colosseum : I have attended Nazi rallies: but I have never seen anything like this. People were shouting, singing, and performing the most extraordinary actions all over the

- p.206

- place, but there was absolutely no sense of a crowd. Each person acted completely on his own, glancing neither right nor left. Some followed with their eyes the man with upraised hands who was slowly, very slowly, turning on his chair: many did not. His tranquil expression, the controlled beauty of his gesture, was a pleasure to watch, but there was no magnetism about it. As for me, I thought of a play by Sophocles performed in classic style, where the actors spoke lines filled with passion from behind immobile masks. The contrast between the swami and his audience had something of the same effect.

- One man flung his arms repeatedly in the air, singing tunelessly. Another danced round and round, a beatific expression on his face, not with the hop, skip and a jump of the Hare Krishna-ites, but with graceful, ballroom steps. He was dancing, I thought, with the girl of his dreams. Another young man took off his jacket, and with jabs of his right and left fists fought an invisible antagonist with all the joy of a boxer punching his way to victory. An American woman, grey-haired, squatted on the ground with her eyes closed, clapping her hands with voluptuous movements. A man who was obviously an office clerk, stripped

- p.207

- his coat, shirt and vest, and stood, immobile, clad only in his flimsy dhoti. At his feet a man flung himself on the ground and rolled about there, like a child on a soft carpet. A pretty girl gyrated slowly, her hands in a seductive gesture, as though she were a fashion-model. One old woman turned her face to the sky, weeping profusely and laughing at the same time. From all over, as the drum pulsed without stop, came a confused sound of voices as people shouted meaningless syllables. Nobody, as far as I could hear, was chanting a mantra. To the rhythm of the drum one man gave violent jerks of his head, left, right, left, right, till I thought he would break his neck.

- The drum stopped. Everybody stood or sat still. ‘ Now, ’ said the swami, ‘twenty minutes of meditation. Be still, be silent, close your eyes. A hush spread across the assembly, which deepened into complete silence. The noises of the city crept back into my consciousness. Some people closed their eyes, others just stared into vacancy. The boxer relaxed his muscles visibly, the frantic dancers sat in utter stillness. There were no whispered prayers, no yoga postures, no mystic gestures of finger and thumb. Only stillness and a great quiet.

- p.210

- The drum started again, a softer, tripping rhythm this time. ‘Now, ’ said the swami, ‘joy. Let us be happy.’ The dancers got to their feet and danced but without frenzy. The boxer stood up, spread his arms, and smiled. The man who had rolled on the ground, stretched himself, still lying horizontal, and laughed. The pretty girl composed her face into an infant ’ s smile. The man who had stripped halt- naked rubbed his torso admiringly.

- The drum stopped for the last time. The swami left his chair and moved to his car, people crowding round him to touch his hands or feet. Assistants moved his chair and put it on the top of a taxi. The swami drove away. An American girl burst into violent sobbing, while her companions watched her with amused smiles. The place of assembly was dotted with prone men and women, exhausted by their experience.

- p.212

- One of the most notable things at the meeting was the respectability of the response to the invitation, ‘ Do what you like. ’ Carnival-time in a Catholic country invariably sees some sights that cause raised eyebrows in even the broadminded: so much so that Carnival is forbidden in Rome because it might shock the pilgrims. But this criticism is not quite fair to Swami Rajneesh. The massmeditation I saw was in a big city. Nudity (for instance) is forbidden within city precincts, even to fakirs. When Rajneesh holds his meetings in more secluded places such as the holy hill called Mount Abu, some of his followers strip naked with all the nonchalance of Western actors and actresses.

- His invitation to freedom should not be taken with undue gravity. It is more like packing the kids off to the swimming hole for the summer afternoon. What is remarkable and new is the second twenty minutes. Whether the audience really meditates or not I cannot say. I can confirm that after the drumming and the frenzy there is that sort of silence which only a great solo musician can command. Even he could not produce that utter stillness: no coughing, no fidgeting. Like the soloist, Rajneesh is there on the platform, gyrating in his chair. But a large number of those in an enviable state of calm relaxation were not even looking at

- p.213

- him. I have heard John Kennedy address a joint session of Congress, my seat being to his right behind him, so that I could observe the audience. He did not produce the stillness of Rajneesh, except from the Justices of the Supreme Court. But they were sitting in the front row, right underneath him and they had longer experience in suppressing yawns and the furtive scratch.

- Nevertheless, Rajneesh ’ s meeting was a public show, as much as those of Billy Graham, though mercifully less verbose. In private, he is close to the true teachings of the Upanishads. He is at pains to point out that to gain the knowledge of the real self, one must be alone. Like the sages, he attacks society in words that are a good deal sharper than those of Marcuse :

- ‘Every type of social institution is a means to kill the individual and convert him into a machine. All our universities are factories to kill the spontaneous - to kill the spark, to kill the spirit and change man into a machine. Then society feels at ease with him. He can be relied upon. He can be predicted. Man becomes predictable as soon as he becomes a machine. We can predict a husband, a wife, a lawyer, a scientist. We know who they are and how they will react. We can be at ease with them.’

- p.214

- He argues that we are all too rational, a philosophical word which is a little too worn to have much meaning. He has improved upon it. He says we over-do. ‘In the world in which you are proficient’ , he says, ‘you tend to over-do. This over-doing is the problem. One must not be an expert all the twenty-four hours. One must also do something in which one is no-one. One must also do something about which one knows nothing. One must be a child, playing sometimes, immature, unknowing, ignorant.’

- It recalls Ramakrishna asking Vivekananda to explain ‘logic’ and then not waiting for an answer.